Earlier this week, the Ghana Boxing Authority (GBA) issued sanctions against two boxers, heavyweight Richard Harrison Lartey and former lightweight world champion Richard Commey.

The GBA found Lartey guilty of forging a release letter that enabled him to fight Fabio Wardley in the UK last November. Lartey was banned for five years, which disallows him from fighting in Ghana or partaking in activities related to Ghana boxing during that period.

Commey received a two-year ban for “false accusations” and “disparaging remarks” made by the fighter against the GBA during an interview with a social media channel. During that interview, Commey railed against the GBA, at one point implying that they were on illegal drugs.

These bans have sparked controversy within the Ghana boxing community and led some to wonder what truly spawned them? BoxingAfrica.com seeks to answer that question and shed light on issues that warrant examination.

FOLLOW THE MONEY

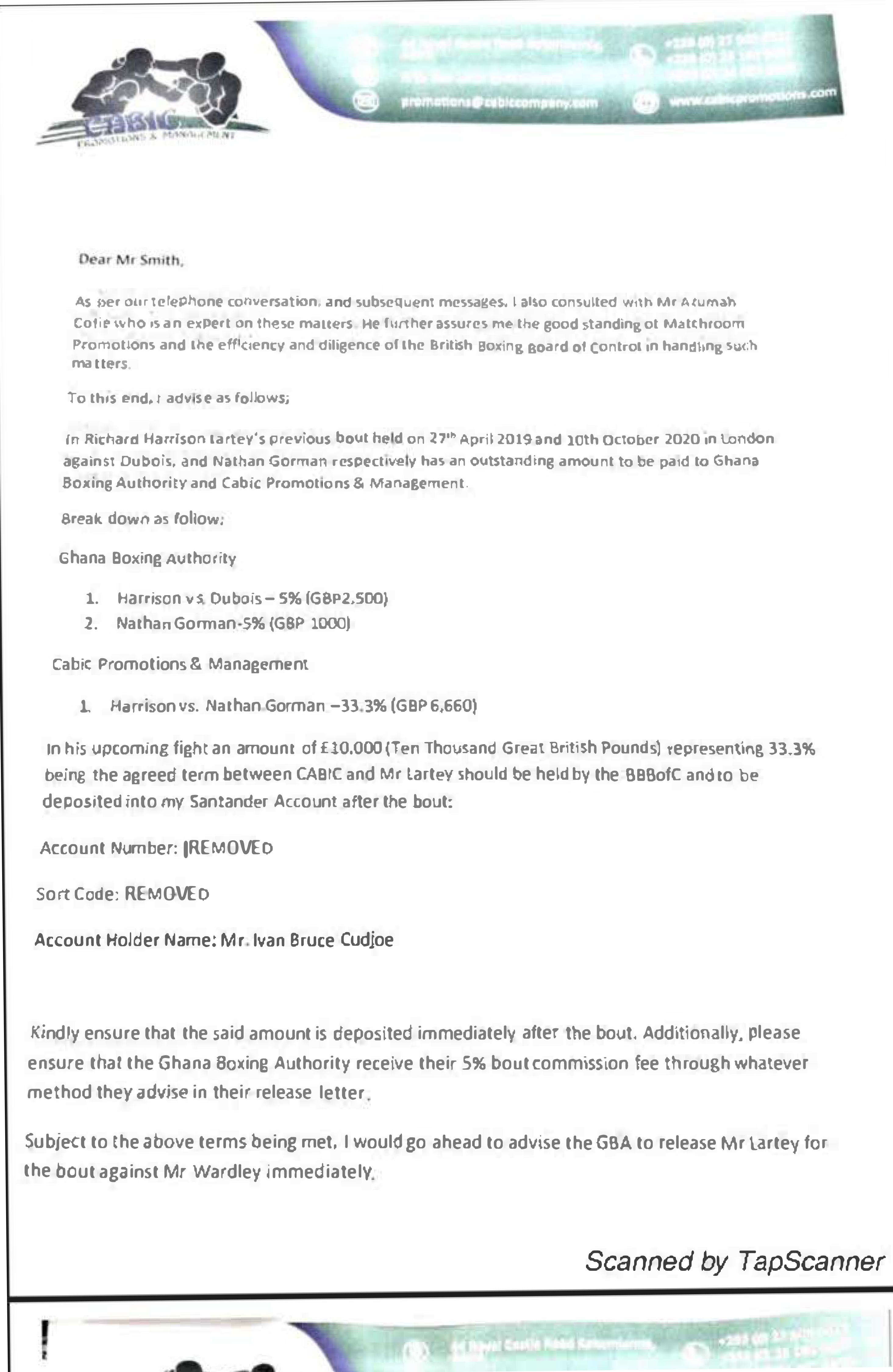

BoxingAfrica.com has obtained documentation which might lead one to conclude that in order to understand Lartey’s issues with the GBA, one must first follow the money (more below). The tension between the two parties began in March 2019, when Lartey agreed to fight Daniel Dubois in the UK. Copies of the fight agreement should have been provided to Lartey, his managers Cabic Promotions, and the GBA. Lartey was the only one who wasn’t furnished one.

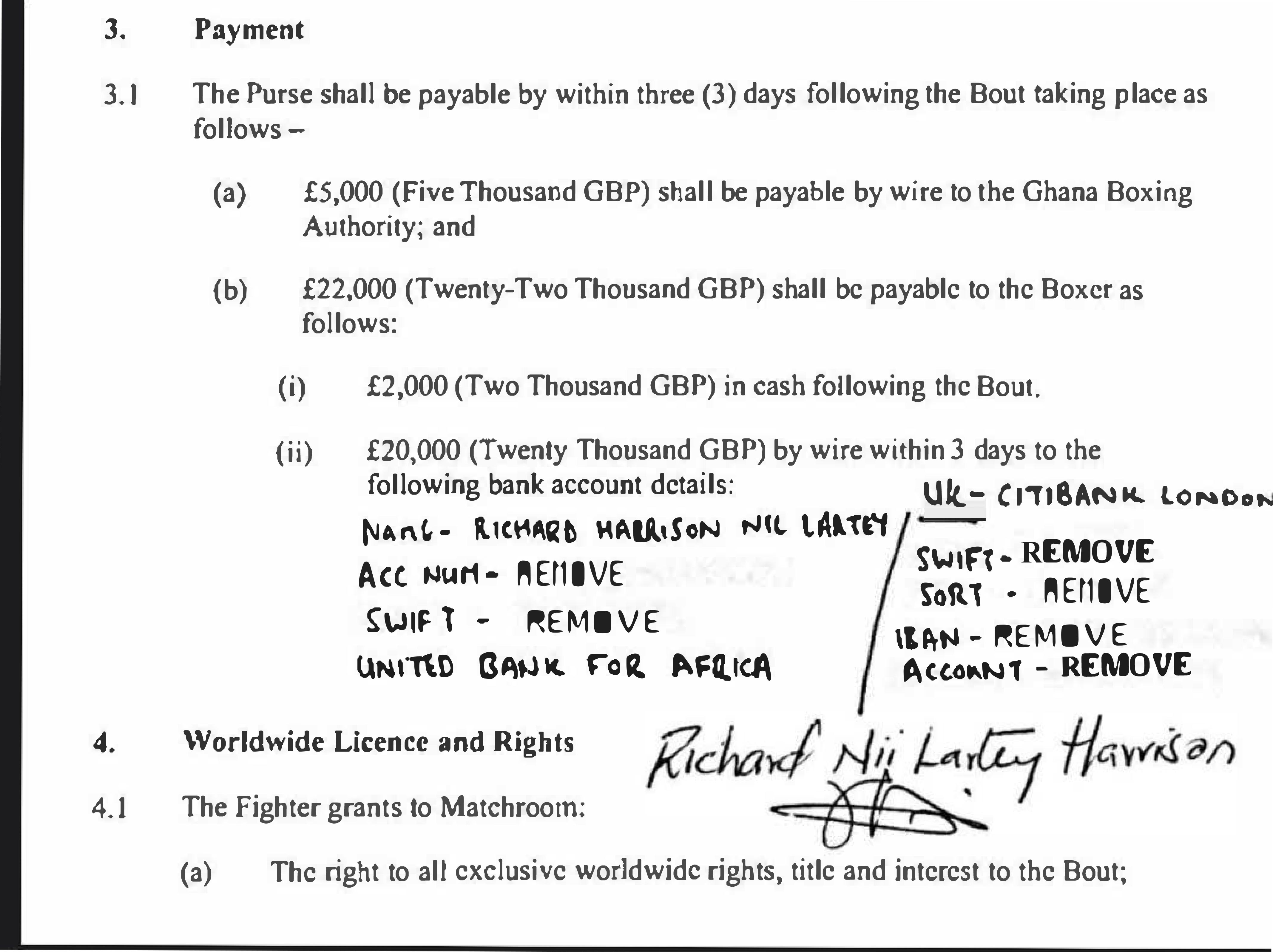

Cabic signed Lartey’s portion of the contract and informed him that he was to be paid £20,000. Harrison later learned that his actual purse was £50,000.

“I kept wondering how they could have done that and what role did the GBA play if they saw the contract?” Lartey pointed out.

Ultimately, Lartey decided to proceed with the bout. He gave a good account of himself despite losing—enough to earn subsequent fights in the UK. The £50,000 purse was wired to Cabic. The managers were to take their contracted 33% split, which would have been £16,500 (leaving Lartey with £33,500). Instead, they offered Lartey only £10,000.

The financial tussle led Lartey to reach out to the GBA to redress the situation. They ignored it for nearly 1.5 years. When Lartey sought a release, Cabic Promotions submitted a letter to Lartey through the GBA, stating that he would have to pay £5 million in order to terminate the contract.

The drama continued with Lartey’s October 2020 fight versus Nathan Gorman, also in the UK. The GBA issued the release for the fight on the condition that Lartey must continue paying Cabic 33% of his purses, despite their prior actions and their absence from negotiating fights that Lartey landed on his own.

Which leads us to today. In November 2020, Lartey agreed to fight Fabio Wardley in the UK. According to the GBA, he forged documentation to obtain the bout.

Lartey vehemently denies this. “I left for the United Kingdom to fight Wardley without a release letter so Matchroom Promotions [promoter of the event] wrote to the GBA to release me for the bout. That was when the GBA directed them to negotiate with Cabic Promotions (whom I have issues with) before they will agree to give a greenlight for me to box.”

According to documents obtained by BoxingAfrica.com, the GBA received £5,000 from Matchroom Promotions; part of their commission for the bout that ultimately earned Lartey a five-year ban. This was done through Cabic Promotions (see documents below).

This begs the question: Did the GBA really care that Lartey obtained the bout without their permission or did they care about not receiving monies from that bout?

“We received that money because it is a requirement for Ghanaian fighters who are released to fight outside but that does not mean we condone the forgery of the release letter,” said Patrick Johnson, executive secretary of the GBA.

If a thief wants to rob a house, would one approve it if he agreed to give you some of the spoils? And would one be in a moral position to punish him afterward? Clearly, the GBA isn’t above profiting from the very action they are condemning.

Speaking of spoils, some have questioned if the GBA’s major issue with Richard Commey is, in part, financially motivated. Commey isn’t licensed by the GBA and fights primarily in the U.S. Thus, he has no fiduciary responsibility to the GBA nor any legal ties to them.

While some say the GBA’s 5% commission for international bouts is understandable, others liken it to a mafia tariff. Given the amount of fights that have taken place over the years, the GBA’s transactions should be transparent. No one is accusing them of foul play. However, an audit of these monies is in order to see how they have been reallocated to uplift Ghana boxing.

A MATTER OF RESPECT

American writer Eldridge Cleaver once said that “Respect commands itself and it can neither be given nor withheld when it is due.” Thus, in order for the GBA to obtain respect, it must place itself in good standing; merely being an organization isn’t enough.

ESPN, the largest sports network in the United States, once described Richard Commey as being low key and humble. Badlefthook.com called him a “good guy” who is “humble and doesn’t make waves.” And just last week, Commey was named goodwill ambassador of the United Nations Association of Ghana Commission for Women and Children Affairs (UNACWCA).

On February 26, Commey first issued a written apology for his comments toward the GBA where he questioned their decision making and concluded that perhaps they were under the influence of illegal substances. One month later, along with manager Michael Amoo-Bediako, he appeared before the GBA and apologized again.

In their statement banning Commey for two years, the GBA described these apologies as “half hearted and not contrite.” They went on to say that they hoped Commey’s “haughty and arrogant posture” toward the boxing fraternity would cease.

If you’re scratching your head, you aren’t the only one. After all, who made it policy that the GBA must be respected—and how is one penalized on these grounds?

As noted, Commey hasn’t fought in Ghana since 2017, is not licensed by the GBA and isn’t required to pay them any portion of his purse. Yet he apologized twice to no avail. Perhaps Commey should have publicly bowed at the feet of the GBA in order to avoid sanctions—or pay them 5% of his purse (although in the case of Lartey, that wasn’t enough either).

The issue of respect permeates throughout these two cases. Regarding Lartey, GBA’s Johnson said, “I don’t have anything against him and all I do is my work. I can tell you that Harrison has shown gross disrespect to the GBA board on numerous occasions.”

It’s unclear why this matters. Boxers all over the world have ranted against boxing’s international organizations, sanctioning bodies, promoters and more. One example was when Ghana boxer Emmanuel “Gameboy” Tagoe made disparaging remarks about GBA president Peter Zwennes’ boxing acumen back in 2018. Tagoe’s comments went unpunished.

This selective decision-making is shameful. According to their own mission statement, the GBA is mandated to seek and safeguard “the common interest of all individuals, groups and stakeholders involved in or associated with professional boxing in Ghana.” If the GBA wishes to uphold its values, it would do well to remember what they are in the first place.